John Sweeney’s Legacy and the Future of American Labor

Written by Joseph A. McCartin

Written by Joseph A. McCartin

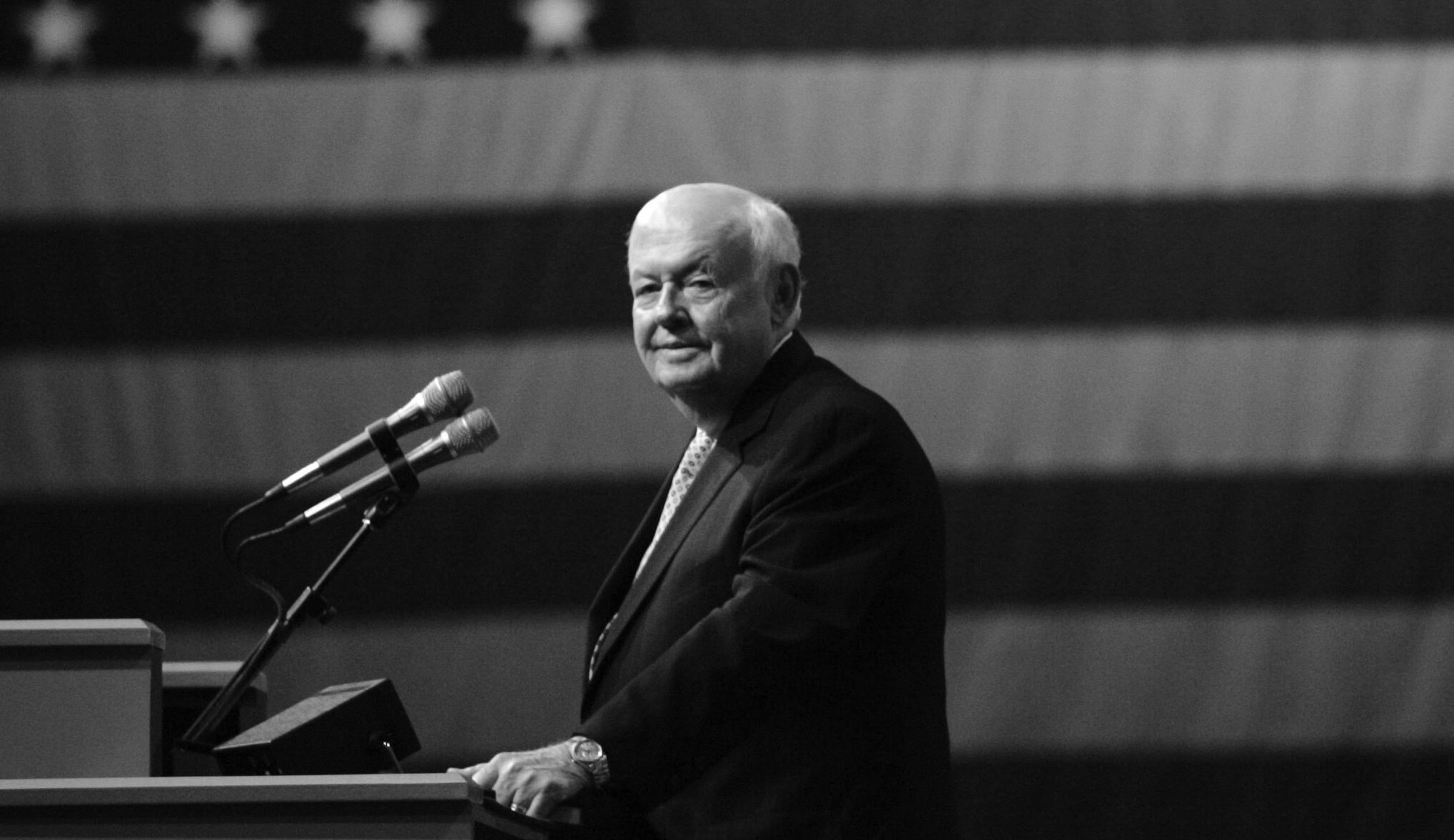

On February 1, 2021 one of the most significant labor leaders of the past century died. The passing of John J. Sweeney at the age of 86 was celebrated not only by those who had worked with or for him, but even by many of his former rivals and critics, which was a testimony to both his stature and the honorable way he conducted himself. But above all, Sweeney was a remembered as the man who fought valiantly to revive the troubled labor movement in the crucial years between 1995 and 2009, when he served as AFL-CIO president.

During his tenure, as the labor movement’s top leader Sweeney emerged as something like the antithesis of the AFL-CIO’s first president George Meany. There is irony in that, for both men shared much. They were born 40 years apart to Irish Catholic parents. Both were raised in the Bronx by fathers who were loyal union men—Meany’s a plumber, Sweeney’s a bus driver. Both became union staffers as young men and rose to prominent positions in the New York City labor movement before heading to Washington, DC, in their mid-40s, Meany to become secretary-treasurer of the American Federation of Labor under William Green, and Sweeney to succeed George Hardy as the president of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). After serving in their respective national positions for fifteen years, each won election to the presidency of the AFL-CIO, Meany serving as the first president of the united federation, and Sweeney serving as the first president to win a contested election for the federation’s presidency.

Yet, if Sweeney’s career mirrored Meany’s in broad strokes, his presidency broke with one pattern after another set during the Meany era. While Meany had once bragged that he had never walked a picket line, Sweeney’s SEIU members famously blocked bridges into Washington, DC, just prior to his election to the AFL-CIO presidency in 1995, and as president Sweeney was arrested several times for engaging in civil disobedience. While Meany moved cautiously on civil rights issues, famously jousting with A. Philip Randolph about the pace of change within the federation, Sweeney insistently pushed the AFL-CIO’s executive committee to change its position on immigration, embracing comprehensive immigration reform in 2000. Meany scoffed at the notion that the AFL-CIO needed an aggressive national organizing operation; Sweeney brought in Richard Bensinger to renovate the AFL-CIO’s Organizing Institute, and called for dramatic increases in union organizing budgets. While the staunchly anticommunist Meany aligned the federation so closely with the objectives of Cold Warriors that its critics took to calling it the AFL-CIA, Sweeney empowered Barbara Shailor to reorganize the federation’s foreign policy apparatus to create the Solidarity Center, which supported a broad range of labor struggles around the world without subjecting them to ideological litmus tests.

Beyond these policy issues, Sweeney counteracted the cultural and political schisms that had isolated the AFL-CIO from allies on the left, on campuses, and in the feminist movement during Meany’s tenure. If Meany’s AFL-CIO had become estranged from the left, Sweeney named the self-identified leftist such as Bill Fletcher Jr. the AFL-CIO’s education director. If the AFL-CIO alienated youthful antiwar protesters’ Left during Meany’s presidency, Sweeney rebuilt bridges to the young with campus teach-ins, a Union Summer immersion program, and support for campus labor solidarity organizations such as United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS). While no women served on the AFL-CIO’s executive council or occupied top staff positions during Meany’s tenure, Sweeney name Linda Chavez-Thompson along with Richard Trumka, to his victorious New Voices ticket in 1995. He also populated AFL-CIO headquarters with women. Along with Shailor, who ran the federation’s international affairs, they included the founding director of Working America, Karen Nussbaum, field mobilization director Marilyn Sneiderman, and communications director Denise Mitchell.

The reform energy that Sweeney brought with him into the AFL-CIO in 1995 had its roots in his background and his tenure at SEIU. Unlike Meany, Sweeney was the son of immigrants. His bus driver father was a CIO unionist—a member of Mike Quill’s Transport Workers Union—and his mother was a nonunion janitor. Both parents’ experience would help shape his later trajectory. Also, unlike Meany, he did not take up his father’s trade. He attended college and briefly considered a career in business, working as a clerk for a short time at IBM, before choosing a life in the labor movement when he was hired in 1956 as a researcher with the International Ladies Garment Workers. Sweeney’s contact with labor priests, like the Jesuit Phil Carey, S.J., encouraged him to consider his union work as akin to a religious vocation—he once considered entering the priesthood—and he remained close to social justice Catholicism throughout his life.

Had Sweeney remained with the ILGWU, a union on the verge of a precipitous decline membership, his ascent to the pinnacle of labor leadership would have been unlikely. But he was recruited in 1960 to become a contract administrator for SEIU Local 32B by a friend and mentor, another Irish Catholic son of the Bronx, Thomas R. Donahue. Ironically, it would be Donahue that Sweeney would defeat 35 years later to win the AFL-CIO presidency. At Local 32B, which represented doormen and maintenance workers in New York City buildings, Sweeney found the room and resources to develop his leadership skills. He showed that he could be both genial and tough, militant and conciliatory, a diplomat or a warrior as the occasion demanded. He skills were quickly recognized. By 1972 he was executive assistant to the local’s president. A year later, he was vice president. And by 1976 he was elected to the local’s presidency. Local 32B was already one of the largest in SEIU, but a year later Sweeney made it larger by merging it with Local 32J, which represented janitors, to form Local 32BJ, the most powerful local in its parent union.

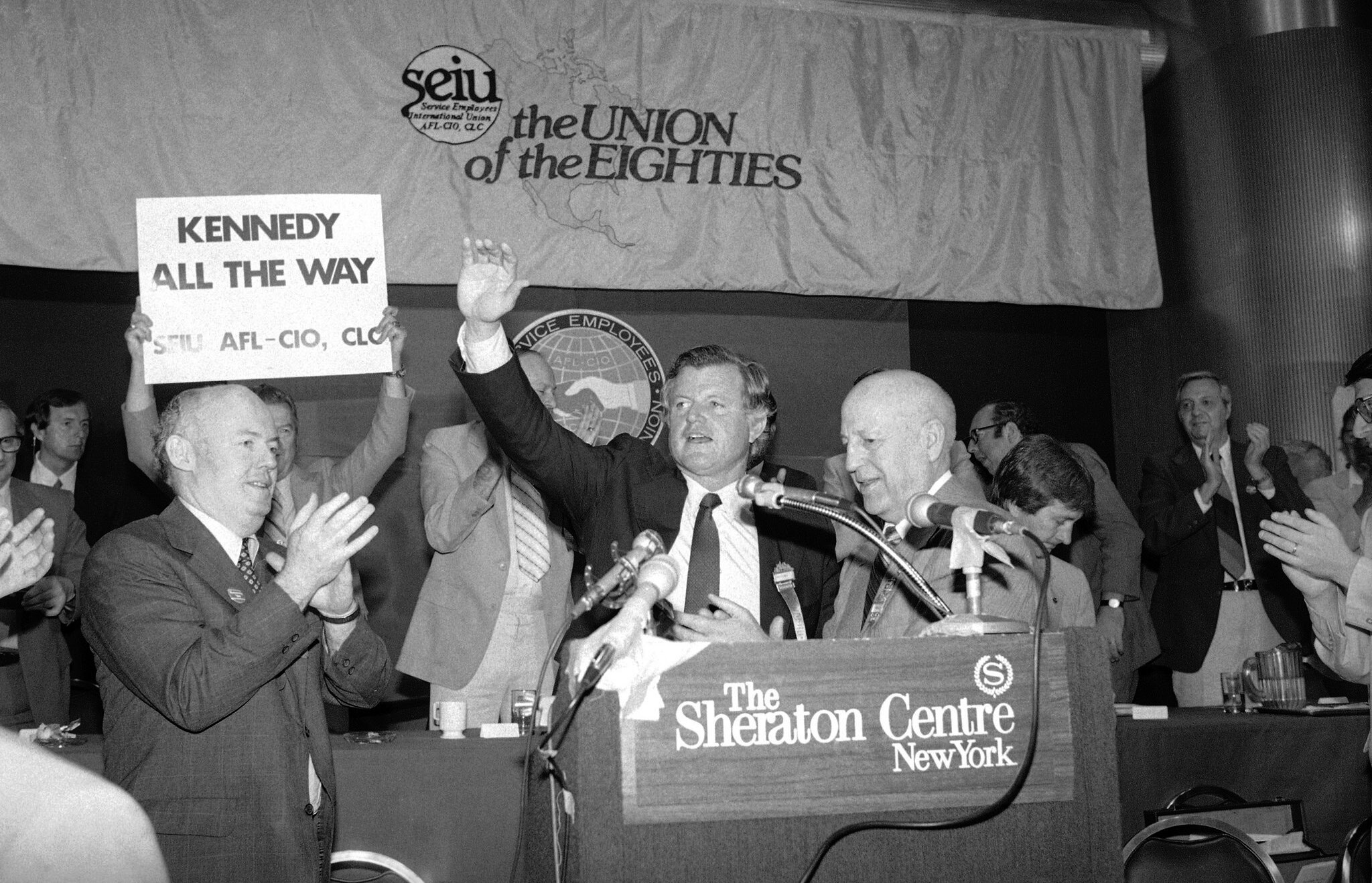

In the 1970s, SEIU was led national by George Hardy, who was determined to expand the union by pushing into public sector and healthcare organizing. The union had dropped “Building” from its name in 1968 to become simply Service Employees International Union, and Hardy succeeded in making it a union with broad jurisdiction. Along with Jerry Wurf of AFSCME and Albert Shanker of the American Federation of Teachers, Hardy was one of the few union leaders whose organizations were growing in the 1970s. When Hardy stepped down in 1980 at the age of 69, Sweeney was elected to succeed him, promising to continue growing the union.

As SEIU president, Sweeney not only continued its growth, he undertook a number of moves that put it at the cutting edge of the labor movement. In 1981, SEIU formed a partnership with National Association of Working Women to form SEIU District 925, which focused on organizing working women. By 1984, Sweeney began restructuring SEIU to prioritize organizing, naming Andy Stern, then of the Pennsylvania Social Services Union, SEIU Local 668, as organizing director. Signaling SEIU’s growing focus on organizing low-wage workers, Sweeney also approved affiliation of locals of the United Labor Unions, an independent union started by the nation’s largest grassroots community organization, the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN). SEIU’s ties to ACORN would grow in subsequent years as the union supported several ACORN campaigns, such as the fight for affordable housing, and ACORN as staffers rose to prominent positions in SEIU (and, following Sweeney’s ascension, in the AFL-CIO as well). The SEIU-ACORN alliance would in turn help plant seeds for later SEIU efforts to organize home healthcare and fast-food workers.

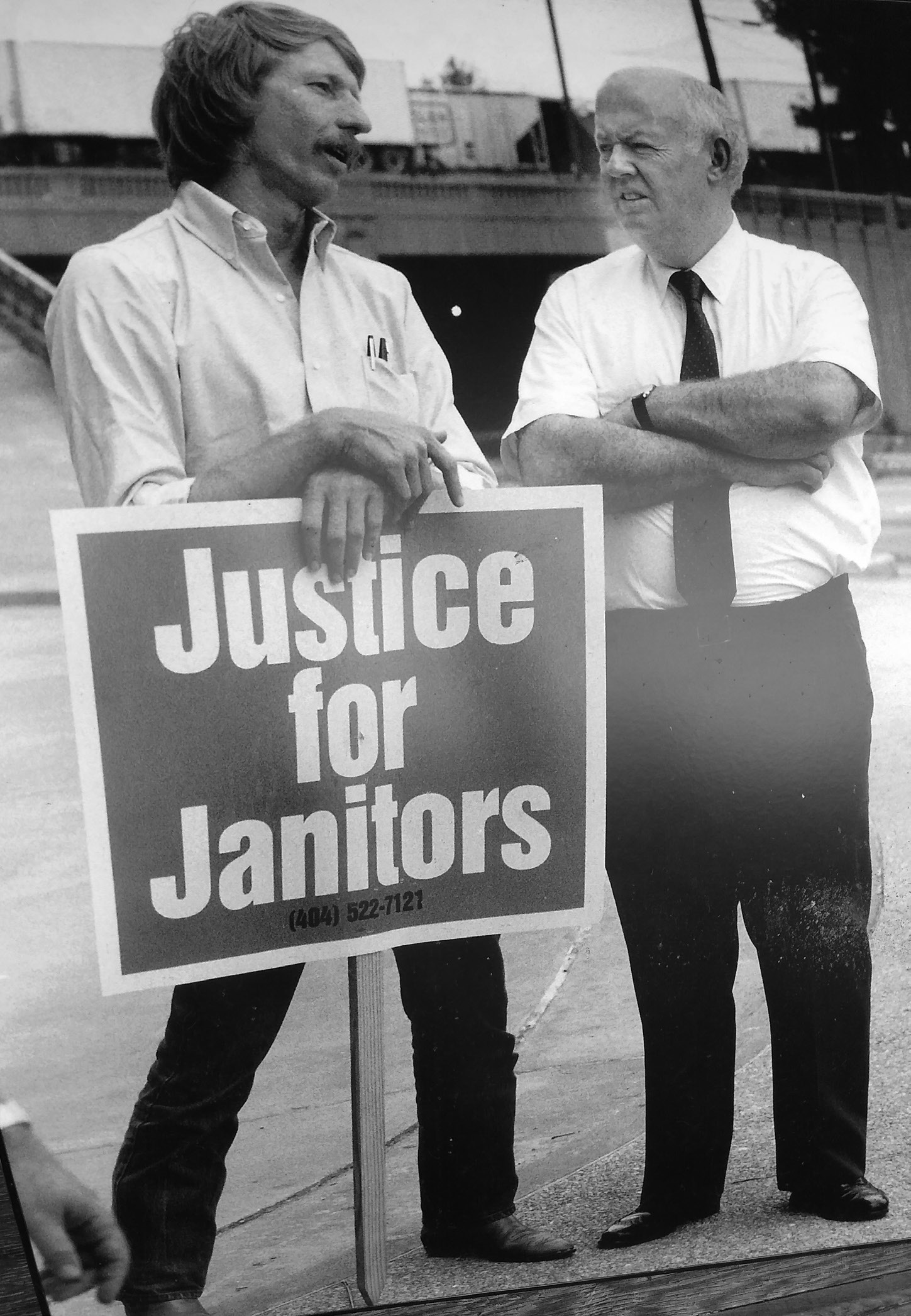

In this period, SEIU also launched what would become its signature campaign. With the memory of his mother’s janitorial work in mind, Sweeney was determined to reverse the deterioration in wages and benefits that afflicted the building service industry between the mid-1970s and the mid-1980s, as office buildings shed directly employed janitors and hired exploitative contractors, who relied primarily on immigrants. Stern turned to a young veteran of the United Farm Workers, Stephen Lerner, to design a campaign that would be known as Justice for Janitors. The idea for the campaign took shape during a bitter strike in Pittsburgh in 1985. Soon the union took it to cities around the country, including Denver, Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, and Houston. The campaign suffered some defeats (in Atlanta in 1988, for example), but it perfected tactics of civil disobedience that placed pressure on the real estate interests that dominated commercial office space in the nation’s cities. After achieving a dramatic breakthrough in Los Angeles in 1990 following a police riot against protesting janitors, the union won contracts in LA and many other cities. Justice for Janitors captured the imagination of the labor movement like no other campaign in its time.

These moves positioned John Sweeney as not only the leader of the nation’s fastest growing union in the 1990s, but its most progressive national figure. While SEIU was thriving, however, the larger labor movement continued to suffer. Lane Kirkland, the loyal lieutenant who had succeeded George Meany as AFL-CIO president in 1979, had hoped that Bill Clinton’s election to the U.S. presidency in 1992 would provide a respite from the antiunionism of the Reagan-Bush years. But the hoped-for turnaround never came. Instead, Newt Gingrich and his Republican allies were swept into power in both houses of Congress by the 1994 midterm elections. Believing that the cautious and unimaginative Kirkland must leave office at the end of his term in 1995, Sweeney joined with several other union leaders to beseech Sweeney’s former mentor, Tom Donahue, who then served as Secretary-Treasurer of the AFL-CIO to challenge Kirkland if he refused to step aside. Donahue, who had served as Meany’s executive assistant before winning the secretary-treasurer’s office under Kirkland, thought it dishonorable to challenge his leader. Sweeney then declared that he would challenge Kirkland, creating the first truly contested election in the history of the labor movement’s leading federation in a century (Mine Workers president John McBride had briefly deposed Samuel Gompers as AFL president in 1894 only to be turned out again in the following year). When it quickly became apparent that Kirkland could not win, he resigned, making Donahue interim president and setting up a fateful confrontation between Donahue and Sweeney at the 1995 AFL-CIO convention.

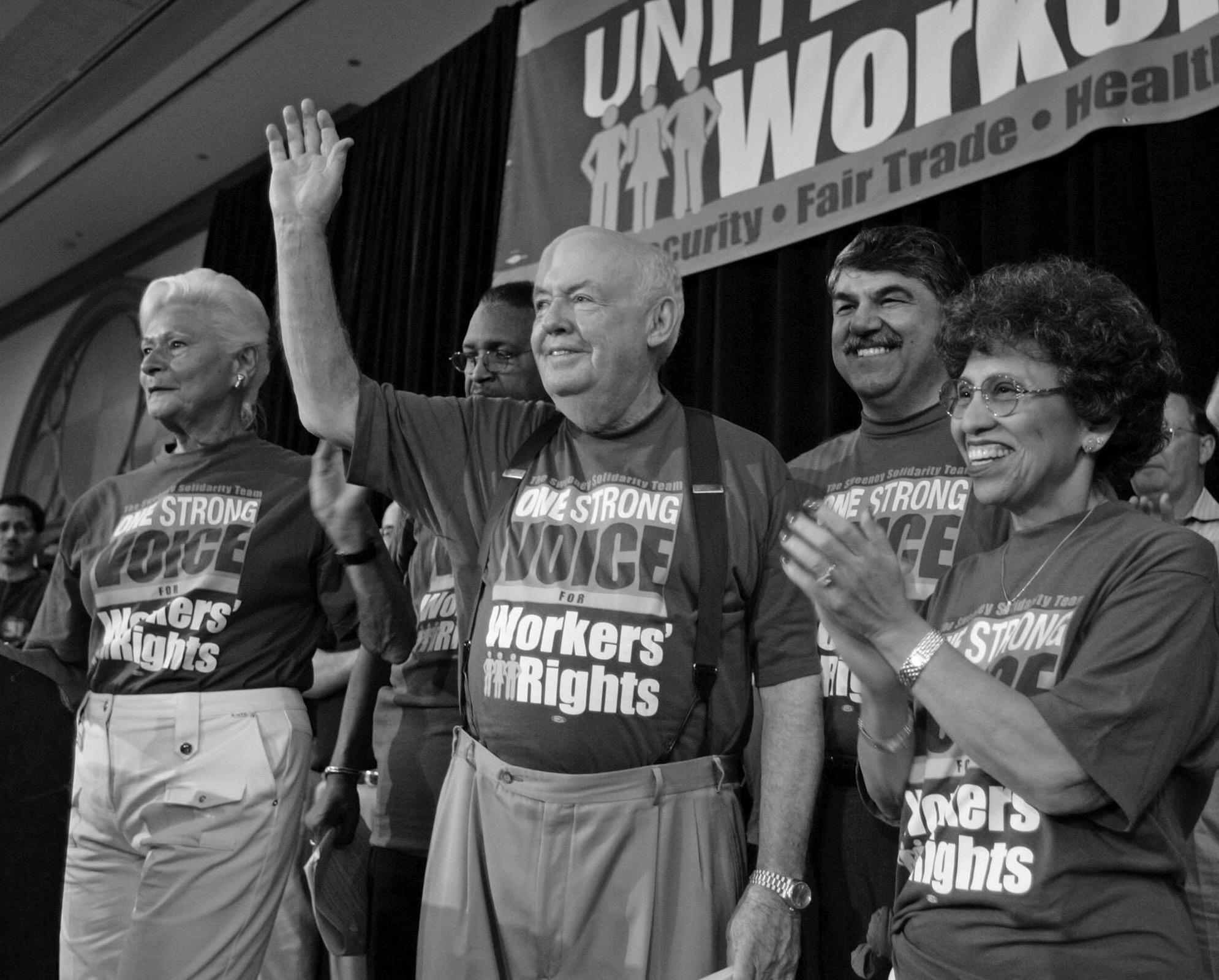

In the debate that took place prior to the delegates’ vote at that convention, Donahue accused his former mentee of blocking bridges (an allusion to recent civil disobedience by Justice for Janitors that had closed bridges into Washington, DC), instead of building bridges, which, he argued must become the union movement’s priority. Sweeney brushed the criticism aside, saying that he would begin building bridges “once the shelling” from anti-union employers and politicians stopped. As Sweeney’s presidency would later show, he began building bridges even as he continued to support blocking them. Not only did Sweeney’s AFL-CIO reach out to women, immigrants, the young, and the left, among others, it built bridges to environmentalists and critics of neoliberal globalization. When the World Trade Organization convened in Seattle in 1999, the AFL-CIO was at the center of the broad coalition that took to the streets in protest of its neoliberal trade and environmental policies.

Not since the rise of the CIO in the mid-1930s, had the labor movement generated as much reform energy as it displayed under Sweeney’s leadership at the turn of this century. Yet, the momentum with which the union movement entered the 2000s did not last. When Sweeney stepped down in 2009 to be succeeded by his onetime New Voices running mate, Richard Trumka, the bright hopes that had greeted his election in 1995 had long since given way to harsher realities and lowered expectations.

There were many reasons why the Sweeney presidency was unable to fulfill the fondest hopes of its supporters. Yet two causes—both central to the rationale for maintaining a federation of unions—stand out. When the American Federation of Labor was created in the 1880s, two of its key concerns were organizing unions more effectively for political action against a hostile government and courts and keeping unions from warring with each other over jurisdiction. By federating, union would be better able to “reward our friends and punish our enemies” at the ballot box, Gompers argued. A federation could also prevent fratricidal conflict, Gompers reasoned, setting up rules to protect its affiliates from the encroachments of their rivals while thwarting “dual unionism” arising from outside of the federation. Yet as the 20th century drew to a close, the limited nature of labor’s political influence and persistent labor factionalism began to undermine Sweeney’s influence. He suffered a major factional defeat in 1998 when his ally, Ron Carey, was disqualified from running for reelection as president of the Teamsters because of an illegal election financing scheme, paving the way for the election of James P. Hoffa, who entered office resentful of Sweeney’s alliance with Carey. Sweeney suffered an even more profound defeat in the political sphere two years later when Al Gore lost the disputed presidential election of 2000 to George W. Bush. The right turn in the nation’s politics occasioned by Bush’s election was further reinforced by the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, which unloosed a range of reactionary impulses. As organized labor struggled to deal with this new and more hostile environment, Sweeney inevitably suffered as the high expectations he helped elevate in the 1990s were brought to the ground.

Just as the Gingrich midterms of 1994 had provided an impetus for Sweeney’s rise to the AFL-CIO presidency, Bush’s 2004 reelection helped turn grumbling against Sweeney into outright opposition. Several of the unions that had backed him in 1995, including his former union, SEIU, now led by his onetime protégé Andy Stern, demanded that Sweeney either support a thoroughgoing restructuring of the AFL-CIO or step down when his term ended in 2005. Backed by a majority of the AFL-CIO’s affiliates, Sweeney refused this ultimatum. Stern then led SEIU, Hoffa’s Teamsters, the United Food & Commercial Workers, UNITE HERE, and the Laborers out of the AFL-CIO to form the Change to Win (CtW) coalition. Fifty years after George Meany had gaveled the united AFL-CIO into existence, labor faced its largest schism since the mid-1930s.

The 2005 split obviously hurt Sweeney, who despite the criticism of his old friend, Tom Donahue, had always prided himself on his skills as a bridge-builder. It pained him that he was unable to repair the rupture that had produced CtW before his presidency ended. Moreover, after having given more encouragement to progressive forces within the broader labor movement than any leader since John L. Lewis, he was stung when CtW rivals—and especially SEIU’s Stern—portrayed him the guardian of an old, failed order. Despite the personal pain this caused him, Sweeney displayed none of the prideful petulance that was a hallmark of Lewis’s personality. That the split between CtW and the AFL-CIO never grew as bitter as the one between the AFL and CIO in the 1930s owed in part to Sweeney’s forbearance and his desire to limit the damage. By 2006, the AFL-CIO was signing “solidarity charters” with locals of the disaffiliated unions to allow their continued participation in local and state labor councils. This moderate approach paid off soon after Sweeney stepped down in 2009, as the Laborers, UNITE HERE, and the UFCW began leaving CtW and returning to the AFL-CIO’s fold. Stern, meanwhile, stepped down from SEIU’s presidency in 2010, and left the union movement behind. If Sweeney harbored lasting animosity toward his onetime protégé for leading the CtW rebellion, he never expressed it publicly. When Georgetown University held an event honoring Justice for Janitors in 2013, a smiling Sweeney stood shoulder to shoulder with Stern and Stephen Lerner for pictures.

Contemplating John Sweeney’s legacy invites us to consider both the abiding qualities of labor leadership and the limited impact that any one person can have in leading a movement as diverse as American organized labor, operating as it does in a nation whose culture, law, and politics have never been congenial to the building of a powerful institutional expression of workers’ demands and desires.

Back in the 1920s, the (then) radical labor educator A.J. Muste observed that most labor leaders must have “divided souls” for they lead complex organizations that must be capable of acting at some times like disciplined “armies” and at other times and like inclusive “town meetings” in which every member feels their voice can be heard. Shifting between the roles of army general and town meeting facilitator, Muste found, was “obviously painful” for most labor leaders. Most were far better at one task than the other, and few preferred the facilitators to the general’s role. Muste should have met John Sweeney. Unlike most labor leaders, Sweeney was as good a facilitator as he was a general, and he excelled in both roles. Nor did he suffer from a “divided soul.” To the contrary, he relished facilitating new voices and expanding the ranks of those who could weigh in in labor’s town meetings as much as he did leading unions in battle for righteous cause. Rather than exhibiting internal contradictions, everything Sweeney cared about was seemingly connected—faith, family, vocation, politics, and simple human caring constituted a seamless garment in his life. He was not faultless as a leader. He was capable of political blunders, such as his unfortunate and unsuccessful endorsement of the aging Richard Cordtz in the election that was held to fill the presidency of SEIU when he ascended to the AFL-CIO’s top slot. Yet Sweeney was as undoubtedly as skilled as any who have ever risen to his level of prominence at executing the basic task of a labor leader, drawing diverse people together, and giving them the tools to win power.

To understand why such a talented leader did not leave behind a richer legacy of accomplishment, we must consider the other factors that have traditionally shaped and limited organized labor’s windows of opportunity. Historically, one of these factors has been the unfolding of transformative events that were beyond the ability of unions themselves to trigger or manage. Over the course of U.S. history, unions have acted opportunistically in moments of crisis such as the World Wars and the Great Depression to accomplish breakthroughs that would not have been possible without the disruptions to the status quo initiated by those events. It was Sweeney’s fate to lead labor in a crucial period of 2000-01 when events undermined labor’s influence rather than strengthening it: the 2000 election and the 9/11 attacks.

Yet if even if Gore had won that crucial election, Sweeney’s ability to influence the course of the labor movement had already begun to encounter the limitations of another factor that hampered his reform project: the structure of the AFL-CIO itself. Much as he cajoled them, many of the federation’s unions refused to make the investments in organizing that Sweeney felt were necessary to turn around labor’s fortunes, and he had no power to compel them to do so for, as the CtW unions showed in 2005, unions always reserved the right to disaffiliate from the federation if they chose. In truth, since Gompers’s time the president of the nation’s largest labor federation has had limited power to shape the direction of the overall movement.

Finally, Sweeney’s crusade to reform and revive the labor movement helped dramatize the increasing dysfunction of the American political system itself. When he assumed the AFL-CIO presidency in 1995, the Wagner Act had just marked its 60th anniversary. Several efforts to reform our aged and failing national labor law had already met defeat. Sweeney would lead the charge for yet one more such effort, the Employee Free Choice Act. But it would suffer the same fate as previous crusades, killed by the inability of its sponsors to muster a filibuster-proof majority in the senate. As his term ended, it was becoming increasingly clear that major labor law reform was impossible without it being linked to the larger cause of a vibrant and broad-based democracy movement.

As we contemplate where we stand in this tumultuous moment, it behooves us to keep in mind three lessons of this remarkable career. Labor cannot afford to miss the opportunity inherent in this moment of disjuncture. Unionists must be prepared to act boldly to seize this moment, knowing that great leaders are powerless without big grassroots movements. And, finally, labor must seek to firmly wed its cause to the project of rescuing and fulfilling the promise of our imperiled democracy itself. For helping clarify these lessons, we owe a final debt of gratitude to John J. Sweeney, surely one of the most impactful labor leaders in U.S. history.

Joseph McCartin is a history professor and labor scholar at the University of Georgetown.