Why Not Empower Lower Income Families to Organize and Resist the Budget Bill?

Written by Wade Rathke

The immense assault by the current Trump administration on federal employees, congressionally funded programs, initiatives from past administrations, immigrants, civil rights, and more has beaten a daily refrain on all of us that is almost overwhelming. It is head spinning and mind blowing. Many are disillusioned. Resistance and protests sometimes seem whack-a-mole. A barrage of lawsuits has been filed, some successful, but many not, increasing frustration, as the myth of the rule of law crumbles. People are furious and poll support for the administration remains low and falling, but nothing seems to stop the tide.

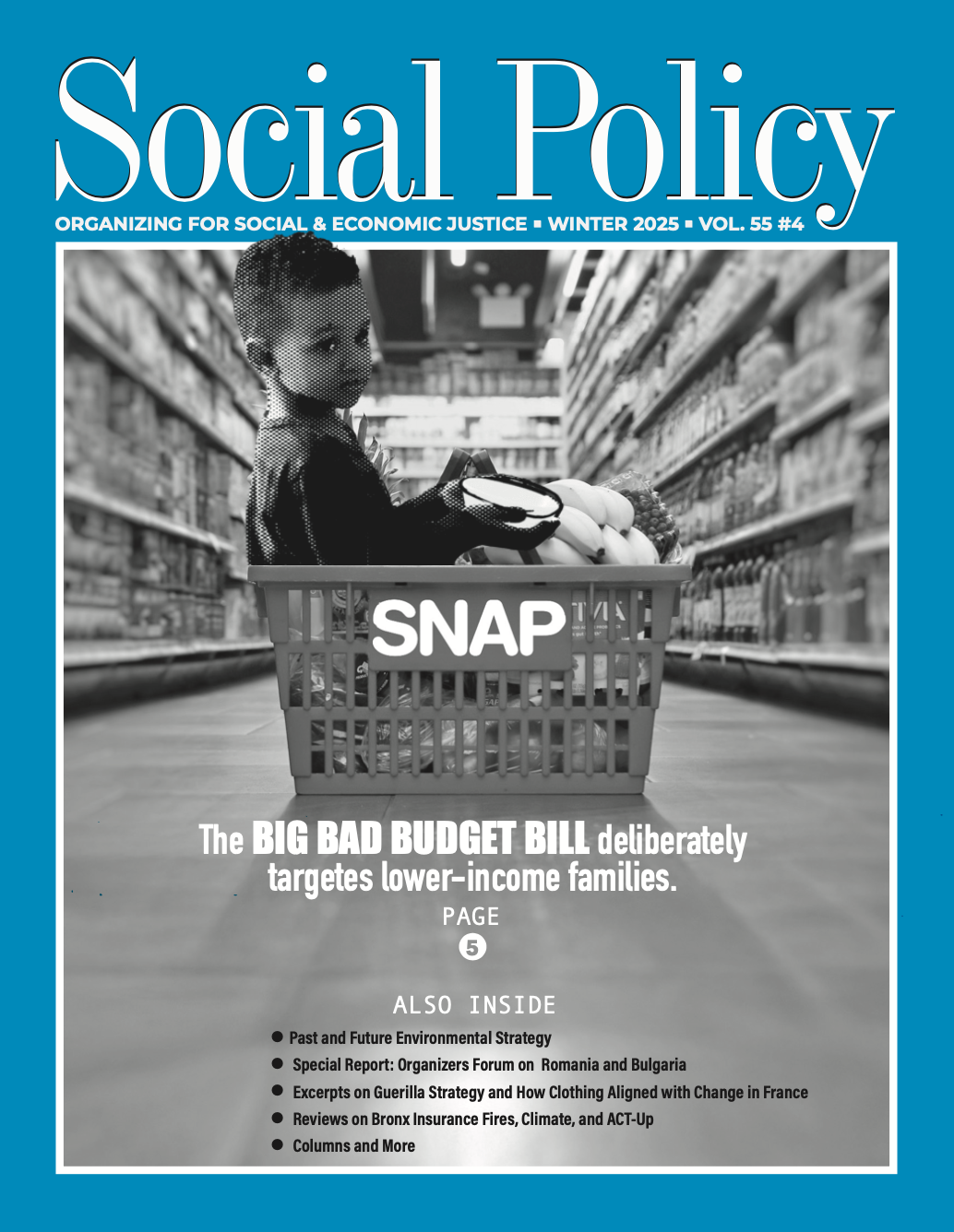

Despite the litany of attacks, lower income families have been targeted disproportionately and aggressively. The Trump and Republican budget reconciliation measure, the so-called Big Beautiful Bill (BBB) has now passed both houses of Congress and been signed by the president. The litany of cutbacks and policy retreats are sweeping in many areas, but in this Faustian bargain of benefits for the rich, the devastating consequences for lower income families are nearly catastrophic. Cuts in food support, housing assistance, and healthcare are extensive with estimates on Medicaid reductions alone over the coming decade ranging from 14 to 20 million people.

As philanthropies raise money for lawsuits, and advocates have launched a steady drumbeat of opposition, there is a vacuum in the opposition: benefit recipients themselves. There needs to be a bottom-up mass response led by lower income families and their own organizations, if the impacts of the Trump attack are to be stopped.

The Ugly Reality and Cynicism of BBB

At the heart of the projected “savings” that the budget bill proposes in exchange for its continued giveaways to the rich are the insertion of work requirements. These requirements would be extended for the SNAP or food stamp program and would be inserted nationally as new determinants of eligibility for Medicaid.

The requirements for Medicaid would be eighty (80) hours of work, education, or volunteer / community service per month. The fiction is that there are able-bodied men and women who should be working and are not doing so. This requirement is designed to either push them into these programs or push them out of these programs. Additionally, certifying eligibility will be made much more difficult. Recipients will have to re-certify every six months, rather than annually. The application process will become more rigorous and laborious. The widely understood objective is to achieve much of the savings with more paperwork, deadlines, on-line access, and other bureaucratic obstacles to eliminate many eligible families and individuals from the programs.

Organizing Handles in these Requirements

Studies indicate that most able-bodied recipients of these programs are in fact already working. Others have been exempt because of their physical condition, personal age, or age of their children. Enrollment in an education or training program may also exempt some. Research has indicated that work requirements do not in fact increase the size of the workforce. There is no surge of new jobs available that this hypothetical workforce is suddenly able to fill. States with high unemployment are allowed to waive the jobs requirement in fact. The most intriguing “handle” in our view is the opportunity to be exempted for volunteer work, which is sometimes defined as community service.

There are some precedents to believe this could work. During the 1978 recession under President Carter, the Comprehensive Education & Training Act (CETA) stepped into the void and qualified thousands of able, but unemployed workers in community service jobs. At the time, there was a requirement that CETA workers could not replace existing city work, but had to be supplemental workers. Many worked under nonprofits as diverse as the YWCA and ACORN, as well as through city agencies like parks and recreation and even sanitation services in cities like New York.

An additional, but narrower, opportunity in the bill might be what are called “Workforce Pell Grants.” Pell grants have long been educational grants (now $7395) to assist low-income students to attend college at various levels. The BBB is slanted against higher education, but favors workforce development, so created this new category. It is unclear at this writing what the grant level will be for what the bill sees as 8-to-15-week courses for professional development. We believe that nonprofits might be able to qualify to train community outreach (i.e. organizers) in such programs and both receive payment for the “school,” as well as use it to qualify some benefit recipients for this number of weeks for educational work. The regulations are not available yet to know how feasible this might be.

In short, we know that volunteer community service will be an acceptable placement for Medicaid and/or food stamp recipients to fulfill these requirements. Could a volunteer program be created and maintained sufficiently to meet the work criteria for both benefits? Could these recipient volunteers -- with support-- create a model and reach the scale necessary to allow program eligibility to be maintained for many lower income families? Could such volunteers create an organization of benefit recipients that is needed now?

Many Questions, Few Answers

There needs to be an aggressive response to this attack on lower income families. It needs to be led by the recipients and families. It needs to enable them to resist the cutbacks and maintain their benefits.

SNAP, the food stamp program, has administered work requirements since 1996 when President Clinton instituted so-called welfare “reform.” The current requirements allow a three-month grace period from July 1, 2023 to June 30, 2026, after which you must verify hours of work, education, or community service. Searching through the existing federal regulations yields no indication of specific requirements for volunteer agencies or any similar guidance or regulations that would instruct a beneficiary how to qualify volunteer hours to maintain benefits. It appeared that the federal government deferred to the states to clarify and promulgate the criteria, if any.

Reaching out to the responsible officials in Ohio, ACORN researchers climbed up and down the bureaucratic ladder. Nothing was covered in any manual. Most officials we corresponded and/or talked with were unfamiliar with any list of approved placements or criteria. Eventually, our referrals led us to ground level case workers. We were given to believe that individual case workers acted with their discretion to approve volunteer hours.

In Pennsylvania, we now have obtained the form the recipient completes and the requirements for a sponsoring agency. The sponsors verify the hours and must be a c3, c4, church, government agency, etc. The is reasonably straightforward. It indicates that the agency needs to register in some way. The Ohio form is even simpler. The recipient fills out the application in the first section and the sponsoring agency fills out the other section. It appears in our research thus far that this constitutes the only current process for community work to qualify in the state for SNAP hours worked. In reviewing applications for volunteer work by recipients in Arkansas and Louisiana, we found similar, simple procedures that we confirmed with case workers.

Having case workers investigate and approve the work, education, and volunteer efforts in a similar manner actually makes sense, even if it does seem an enormous amount of discretion. Historically, many entitlements are self-certified unless and until it was investigated on the presumption of fraud or in random checks. The system currently being designed, which seeks to disqualify more eligible applicants and existing beneficiaries, may tilt the scale against the individual, but likely the burden still lies there. Certainly, it is on the shoulders of the applicant or existing recipient to provide proof of employment for the necessary hours. Likewise, the individual would be expected to provide proof of enrollment and attendance at an educational or training institution to qualify on that score. Rather than Ohio and the other states being outliers, their responses align with the likely reality. To qualify, volunteer hours, a recipient or applicant would submit the information on the nonprofit, explain their volunteer assignment, and their work schedule to fulfill the hours. Presumably, since they will be required for Medicaid to recertify every six months, they would provide proof that they in fact volunteered for the hours required from the agency with whom they volunteered. This proof would be certified by the nonprofit agency.

If qualifying for volunteer time to fulfill the work requirement is therefore driven by the recipient base rather than the state bureaucracy, making such a program work would shift the burden of the project to mass recruitment of “volunteers.” This program could be implemented like other kinds of mass recruitment. Volunteers could then be allocated to a consortium of nonprofits with procedures that certified the position and verified the hours. Many organizations have experience with mass recruitment campaigns using community contacts, mass flyering, radio public service announcements, and social media among other techniques. Doing “tabling” or “stalls” near hospitals, neighborhood groceries, health clinics, and offices where applicants and recipients congregate would all work, along with community meetings, announcements from the pulpit, ads in community broadsheets, and more. Schools may also be venues for recruitment since the BBB also eliminated the automatic eligibility for free school lunches, when you received food stamp benefits, forcing parents to register for free and reduced-price school lunches in the future.

In short, this is something community organizations know how to do and have done frequently in jobs, housing, welfare, and other campaigns. What we don’t know of course is what the response would be, whether or not there would be resistance, or at what point the resistance might come?

More importantly, the existing requirements in the food stamp program provide us a way to act now to assure that the entire project could work later, because it could be field tested. Test projects in pilot states over the coming six months to could qualify recipients within the food stamp program to prove the concept and harvest a small number of volunteers.

There is also a reasonable expectation, because this devolution to the states is another unfunded mandate, that it will be more cursory than complicated with the government hoping recipients fail under the burden, rather than actively having to disqualify them. States are already worrying about outdated computer systems and inadequate staffing. States are also threatened with severe financial penalties for the number of errors in their benefit delivery.

Doubling the Volunteer Impact

We know this is going to be a difficult rollout, whenever it occurs. Many of the cuts are based on experiences in Arkansas in 2018 and more recently Georgia where work requirements were imposed based on waivers granted by the federal government. Although there was no evidence that the workforce increased, there was extensive evidence that the process of applying and maintaining benefits was responsible for reducing the number of program beneficiaries. In Arkansas, before the program was stopped, 18,000 people lost their Medicaid benefits during 2018, despite continuing to be eligible based on their income. The Arkansas experiment was ended by a federal judge in 2019 who found no rationale for the work requirement in the Medicaid rules. The process for proving work and certification was online, despite the gaps in internet access or digital familiarity and comfortability of recipients. Timelines for filing were rigorous and many simply missed filing and appeal deadlines. There were no navigators for applications, maintaining benefits, or filing and assisting on appeals, when there were denials.

Incidentally, Arkansas once again requested a waiver in late January, after Trump’s inauguration in order to impose the work requirements once again. Arkansas at the time sought the waiver by correcting the “faults” in their earlier administration. According to the Arkansas Advocate report on their filing:

It costs Arkansas more than $2.2 billion annually to support the roughly 220,000 “able-bodied, working-age adults” on ARHOME, an estimated 90,000 of whom are unemployed, according to the letter. If the waiver is approved, the work requirement would apply to Arkansans ages 19-64 who are eligible through the new adult expansion group, have an income at or below 138% of the federal poverty level and are covered by a qualified health plan, according to the waiver request.

Learning from past issues with the program, state officials said the new waiver differs from previous work-requirement attempts in that it removes the burden of reporting requirements from recipients through the use of data matching. Data matching refers to the practice of comparing different sets of data to identify similarities and relationships.

Additionally, state agencies will use multiple forms of communication to connect with recipients, and when beneficiaries fall out of compliance, they will be suspended from the program instead of disenrolled, state officials said.

It takes no imagination to believe that many states will try to use untested artificial intelligence to do this data matching. The impact will likely be horrific.

With an appropriate sponsoring agency or coalition of nonprofits, recipients could be certified as volunteers to maintain their own eligibility and to assist other recipients in the process of maintaining their eligibility from first application to recertification to appeals, if necessary. Recipients could be leaders of their own “volunteer” army of sorts.

Is this realistic? We believe there are significant reasons to believe the answer is a resounding yes, based on the experience of many other organizations as well.

In the first-year rollout of the Affordable Care Act, we were part of the navigator’s program in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas working in coalition with Southern United Neighborhoods and Local 100, United Labor Unions. We hired from our memberships and constituency, and signed up tens of thousands for the program, while it existed, and we were a contractor. This experience was duplicated all over the country.

Organizations like the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO) trained recipient leaders and members for exactly these purposes. Many state chapters in the late sixties and early seventies had volunteer members in welfare centers and offices solely to help and advocate for new applicants to enroll in welfare programs, respond to questions from existing recipients, and assist as advocates and representatives on appeals. They knew the program and the welfare manual from their own experiences. For the most part, organizers never had to do this work, because the AFDC and GR recipients were the best and most effective “jailhouse lawyers,” if you will.

Needless to say, the whole stewarding system in workplaces under union contracts also offers another example of how this could successfully work. Worker members learn their contract specifics and the employer handbook and rules and are apply to represent their members on a daily basis. In Local 100, we have even begun putting contracts and handbooks on a “100 Bot” utilizing ChatGPT, so that members and steward can query both right on their phones without needing to contact the union representative or office.

“Project in a Box” – Building a Model

The Congressional window for disgorging eligible recipients from these entitlement programs in order to finance continuing tax breaks for the rich and other parts of their program is ten years. It is reasonable to assume that many states will begin haltingly with stops and starts. The BBB also allows states to ask for extensions in rolling out the programs. With elections in 2028, some might even try to delay for a new administration or be encouraged to do so.

These assumptions, if correct, would allow for more moderate demonstration projects that could be launched in various locations, prove the concept, and build a model, so that it might be scaled up more broadly, might seem more practical, more easily implemented, and more modestly funded.

Pilots would build coalitions but look to handle a limited number, perhaps no more than one-hundred (100) volunteers under its auspices, even while creating a coalition of nonprofits interested and willing to accept and manage volunteers from the recipient base for its usual and core programs with a goal to process and maintain no more than one-thousand (1000) volunteers via such referrals. The volunteers within the primary formation would be sought for outreach, information, and education within the regulation guidelines. They would be tasked to coordinate and organize events to help people apply for benefits, satisfy recertifications, and assist in navigate in person and online.

The project would design in-person and online training tools. A bot would be built for the project that would be uploaded with the regulations, forms, Q&A’s, and other information state by state as they are promulgated. This application would be accessible to volunteers via their phones that would allow them to respond to many situations independently without additional support backup.

Other interested groups could be offered the webinars, tools, and training to evaluate whether a similar program might be applicable in their areas. Training and support would be offered to community action agencies, head start programs, food banks, employment centers, housing assistance centers, community development corporations, housing projects, LMI community organizations, VITA tax centers, and similar agencies to that their staff could also assist their clientele directly or with support from the project.

Outreach would be made to health centers and hospitals that service significant numbers of Medicaid and SNAP recipients. Training would be offered to their patient assistance liaisons, but permission would also be sought for regular tabling or stalls in these facilities to assist access and retention of benefits. The same would be done in grocery stores located in census tracts where LMI families are concentrated, as we discuss in more detail below.

We recognize that no matter how much experience we have in this area from welfare rights organizing more than 55 years ago to loan counseling under CRA that put six million families into home ownership to navigation under the Affordable Care Act that enrolled tens of thousands, no one organization or effort can successfully assist millions of claimants in accessing and protection benefits to which they are entitled. The purpose of building a model is, by definition, so it can be widely replicated. To meet the challenge of the budget bill we need to build a model that can create a movement of support to guarantee the rights of this constituency.

Unlikely, But Possible Partners

There’s a flip side of the coin in the transfer of resources from the poor to the rich. If the billions in savings achieved by pushing people off the rolls for food stamps and Medicaid is successful that also means that companies and institutions responsible for selling food and dispensing healthcare will also lose the same amount in income as the benefit recipients are losing in income.

The estimates for reductions in just the SNAP program are $300 billion. Verified purchase data finds “…for SNAP users, Walmart leads in SNAP shopper spend (24%), followed by Kroger (8%), Costco (6%), Amazon (5%), and Sam’s Club (4%).” The math is straightforward. Over the same number of years, Walmart would lose $72 Billion, Kroger $24 Billion, Costco $18 Billion, Amazon $15 Billion, and Sams – a Walmart subsidiary -- $12 Billion. Over the last 15-20 years as big grocery chains have embraced SNAP income and been certified to receive SNAP dollars, the expenditures of eligible families have become huge income generators for these companies.

What’s true for the big dogs, is even truer for the small ones like the bodegas, the mom-and-pop neighborhood stores, and the smaller chains from the ubiquitous Dollar Stores to regional players. How is it not in all of their self-interests in their own bottom lines not to have eligible recipients retain their benefits? Looking at the publicly available list of over 230,000 establishments that are SNAP certified by the USDA, why would many of them not be potential, even if unlikely, partners, whether active or passive, in an effort to assure that eligible recipients continue to be able to purchase the food stuffs that they purvey?

In welfare rights, we were often able to set up a table inside the waiting room of the welfare center which a recipient would maintain on a regular basis to answer questions, provide advice, advocate, and represent other applicants for benefits. At NWRO in its heyday, in some jurisdictions like New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts we won these rights directly or in court, but even without winning a legitimized physical presence, nothing could stop another recipient from sitting in the waiting room with an NWRO button on and giving assistance to others. A Walmart might not let a table inside the store, but they might allow a stall outside the entrances, as they do for Girl Scout cookie sales, veterans organizations, and other fundraising groups. Even if they did not, others likely would welcome such an effort.

An analogous argument can be made for public and rural hospitals, also being crippled by the claw back of monies that previously were committed to support healthcare institutions who served significant populations of eligible Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries. Hospitals, community health centers, and other healthcare institutions also have a self-interest in continuing to have eligible recipients navigate the process. Many large hospitals under the requirements of the Affordable Care Act have had to clarify their notices and support for providing charity care and bill reduction programs, and even have staff in many big urban hospitals specifically detailed to satisfy these requirements. Why would they not encourage efforts to partner to maintain benefits to eligible recipients?

Furthermore, there is precedent here as well. In the 1980s, ACORN won a suit in federal court maintaining that the waiting room in Parkland, the giant Dallas public hospital, was a “public forum” allowing us to set up a table to assist people trying to navigate the system and charity care. The decision still stands and wasn’t challenged. Once again, with or without a formal presence and a stall or table, trained volunteers that were identifiable could be available in the waiting rooms to assist people in retaining their eligibility and navigating the paperwork.

All of this is important, because even succeeding in training hundreds or thousands of volunteers, they have to be able to access the population of current and future eligible recipients. Constructing an outreach and advocacy program that enlists and/or involves institutional and corporate beneficiaries in the same way as it does eligible recipients increases the efficiency of the program and its reach throughout the population.

Building a Recipient Organization

What we really need in the United States now is the establishment of a rights-based recipient organization that is not advocate or activist-centered, but of, by, and for recipients themselves. The fact that there has not been an effective national organization of recipients to organize against these changes at the local, state, and national level is part of the reason that politicians and policy makers believe that they can conduct this war on the poor without fear of widespread opposition.

The National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO), founded by Dr. George A. Wiley, was such an organization in its heyday from 1966 until several years past his death in 1973. Organizations like ACORN, founded initially as part of NWRO in 1970, and operating at large scale until 2009-10 when reorganized as ACORN International and under various successor names in a dozen or more states thereafter, were able to fill part of that gap on some issues, but not all. Over the last fifteen years, there has been a vacuum nationally in terms of an organizational vehicle where recipients are able to have voice, protect their rights and entitlements, and attempt to build sufficient power to pushback against repression and win improvements in the programs.

We envision one of the tasks for recipients as volunteers would be to engage in the outreach necessary to build an organization of recipients to fill this void. Such a constituency and membership-based organization will be essential over the next decade in winning the necessary reforms in policies and procedures to protect and rebuild the safety net for all, regardless of income.

Wade Rathke is Chief Organizer of ACORN International, but before founding ACORN in 1970 was an organizer for the National Welfare Rights Organization in Springfield, Mass. and served as head organizer of Massachusetts Welfare Rights Organization. He was also chief organizer of Local 100 United Labor Unions when the union acted as a navigator in Texas and Arkansas in the first year of enrollment for the Affordable Care Act.